As AI technology enters 2026, the buzz is rapidly shifting towards multi-agent system architecture. Enterprises are increasingly adopting agentic systems to handle complex, long-running, and tool-driven workflows, such as multi-agent systems.

- What is a Multi-agent System?

- Why Are Multi-Agent Architectures a Hot Topic in 2026?

- What is the Difference Between Single-Agent and Multi-Agent Architecture?

- What are the Components of Multi-Agent System Architecture?

- Communication and Coordination in Multi-Agent System Architecture

- How does Memory Work in a Multi-Agent Systems Architecture?

- Security and Governance Considerations for Multi-Agent System Architecture

- Multi-agent System Architecture Framework Selection Guide 2026

- FAQs

Blog Overview

- Multi-agent systems address the fundamental limits of single-agent AI, especially in long-horizon, tool-heavy, enterprise-grade workflows, where planning, execution, and validation should be separated.

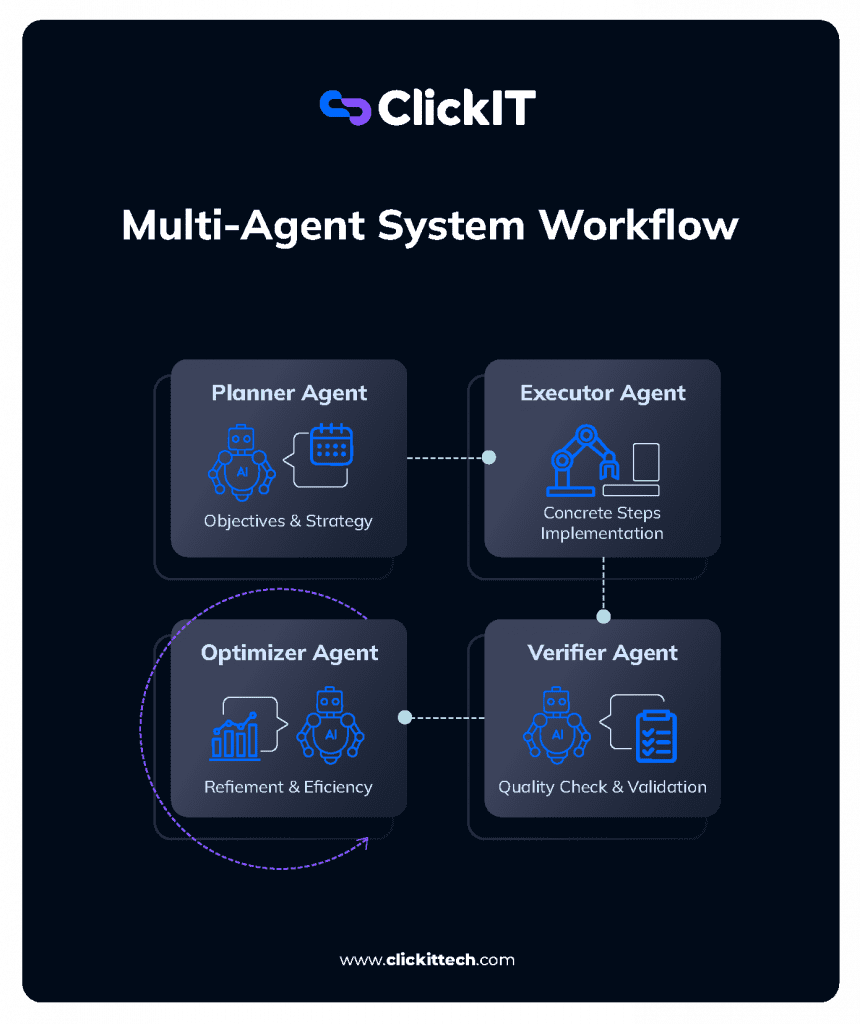

- Role-based agent design (Planner, Executor, Verifier, Optimizer) mirrors human team structures. This approach significantly improves reliability, interpretability, and maintainability in production environments.

- Effective orchestration, communication, and memory architecture are critical for success. Without structured coordination, shared state management, and feedback loops, multi-agent systems quickly become unstable or costly.

- Security, governance, and observability are non-negotiable for enterprise adoption. This can be addressed with least-privilege agent design, robust logging, loop prevention, and human-in-the-loop controls.

- The rapid maturation of agent frameworks and infrastructure has lowered adoption barriers. From being experimental, mult-agent systems have now been transformed into practical, scalable, and production-ready architectures.

What is a Multi agent System?

A multi-agent system (MAS) is a software architecture framework in which multiple autonomous entities known as agents work together either collaboratively or competitively to achieve individual or shared goals within a common environment.

In a traditional monolithic system architecture, agents are dependent on each other. On the other hand, a microservices architecture comprises agents that are independent and modular. Interestingly, in a multi-agent system architecture, agents are independent and yet interdependent.

Here, each agent is typically an intelligent and goal-directed software program entity capable of perception, reasoning, decision-making, and action.

They maintain their own state, objectives, and execution loops, while communicating with other agents through well-defined protocols such as messages, events, or shared memory. This allows the system to solve complex problems by decomposing them into smaller, specialized tasks and each task is handled by an agent optimized for that role.

For instance, consider a simple MAS for traffic management. In this system, one agent controls traffic lights while another monitors vehicle flow. A third agent predicts congestion based on data feeds. And, all these agents work in tandem to optimize urban mobility.

Agents in these systems can be homogeneous, that are all similar, or heterogeneous, specialized for different tasks. They are often powered by large language models (LLMs), reinforcement learning, or rule-based logic.

Why are Multi-Agent Architectures a Hot Topic in 2026?

The concept of multi-agent system architecture traces its roots to distributed artificial intelligence (DAI) research in the 1980s and 90s, which has since evolved significantly.

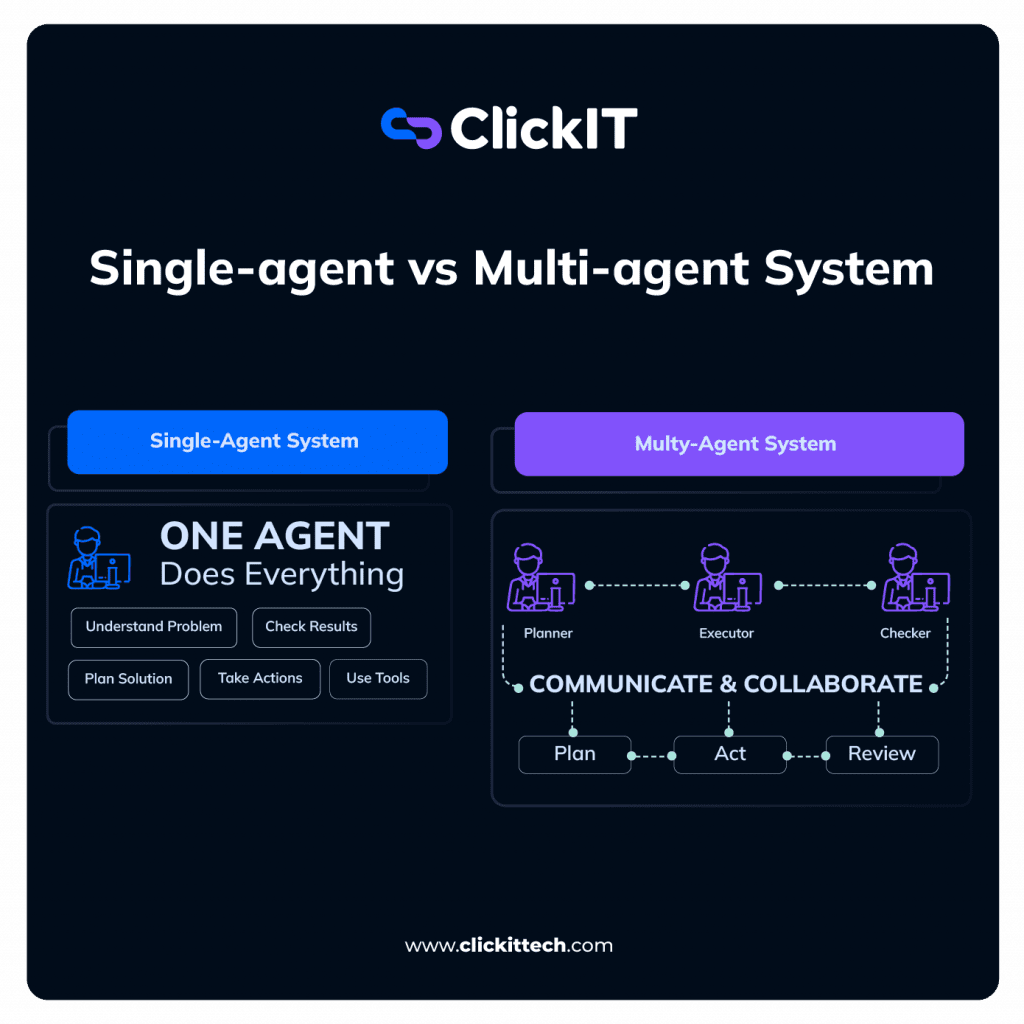

In a single-agent system, we rely on a single entity to handle everything. MAS distributes tasks, enabling scalability, fault tolerance, and emergent behavior.

Gartner reported a 1,445% surge in inquiries about multi-agent systems from early 2024 to mid-2025. This indicates explosive interest from enterprise architects and decision-makers.

Here are a few key reasons for this popularity:

1) Limitations of Single-Agent Systems

Early LLM applications relied heavily on single-agent and prompt-driven workflows, which are effective for simple tasks.

However, these systems struggled with tasks such as:

- Long-horizon reasoning

- Multi-step planning and execution

- Tool orchestration at scale

- Self-correction and validation

As AI use cases expanded into areas like software engineering, data analysis, customer operations, and enterprise decision-making, it became evident that one agent cannot reliably do it all.

The multi-agent system architecture addresses this challenge by distributing cognitive load across agents with focused responsibilities.

2) Real-World Problems Are Inherently Multi-Role

Most real-world workflows, like planning, execution, review, and approval, already involve multiple roles. Multi-agent architectures map naturally onto these patterns.

In 2026, organizations are following multi-agent systems wherein:

- One agent plans

- Another executes

- Another verifies

- Another optimizes

This approach mimics human team structures. Moreover, this separation of concerns improves robustness, interpretability, and maintainability, especially in high-stakes or regulated environments.

3) Tool-Heavy AI Requires Coordination

Modern AI applications rely on a growing ecosystem of tools. There are databases, APIs, vector stores, CI/CD pipelines, observability platforms, and business systems to manage. Coordinating these tools through a single agent often leads to brittle logic and prompt overload.

Multi-agent architectures facilitate dedicated agents for tool interaction with clear ownership of external dependencies. Parallel execution and faster turnaround times are a big advantage here. This is particularly valuable in enterprise settings wherein workflows span multiple systems and data domains.

4) Advances in Agent Frameworks and Infrastructure

Earlier, organizations were apprehensive about adopting multi-agent systems owing to management complexities. By 2026, agent frameworks, orchestration layers, and observability tooling have matured significantly.

Developers can now define agent roles declaratively, monitor inter-agent communication, and easily trace decisions across agents. It is easy to evaluate agent performance independently as well.

This infrastructure maturity has lowered the barrier to adopting multi-agent systems, making them practical rather than experimental.

5) Alignment, Safety, and Reliability Demands

Today, AI systems are entrusted with more responsibility. As such, verification and governance become non-negotiable.

Multi-agent systems support built-in checks and balances:

- Critic agents can challenge assumptions.

- Validator agents can enforce constraints.

- Red-team agents can simulate failure modes.

This layered approach improves reliability and aligns well with enterprise risk management practices.

What is the Difference Between Single-Agent and Multi-Agent Systems?

| Criterion | Single-Agent System | Multi-agent System |

| Agent | One | Multiple |

| Architecture | Can be lower for specialized, smaller models or higher for coordination overhead | Modular, role-based agents (hierarchical, sequential, parallel/swarm, etc.) |

| Reasoning | Shallow, linear | Deep, iterative, distributed |

| Scalability | Limited | High, parallel execution |

| Reliability | Single point of failure | Fault-tolerant |

| Observability | Low | High |

| Context Management | Unified, continuous | Distributed; requires explicit sharing, summarization, or memory |

| Latency | Low to Medium | Medium–high (orchestration, coordination, error handling) |

| Token / Cost Usage | Lower for simple–moderate tasks | Can be lower for specialized smaller models or higher for coordination overhead |

| Best Use Case | Simple tasks | Complex, real-world workflows |

To understand the importance of a multi-agent system architecture, we should compare it with a single-agent system. Both aim to solve intelligent tasks but vary fundamentally in terms of structure, scalability, reliability, and problem-solving approach.

a. Architectural Structure

Consider a task life cycle that comprises understanding the problem, planning a solution, interacting with tools, executing actions, and validating results.

In a single-agent system, reliance is placed on a central agent. All reasoning and decision-making are concentrated in a single control loop. While this design is straightforward and easy to prototype, it tightly couples multiple responsibilities into one agent.

As task complexity increases, the agent’s prompts, context windows, and logic often become bloated, making the system harder to debug and extend.

On the other hand, a multi-agent system decomposes responsibilities across multiple agents. Each agent has a clearly defined role and collaborates through structured communication.

This modularity aligns with well-established software engineering principles, such as separation of concerns and loose coupling, and enables the system to evolve easily over time.

b) Reasoning Depth and Task Complexity

Single-agent systems perform reasonably well for short and well-defined tasks, linear workflows, or when tool usage is minimal.

However, they struggle with tasks that involve multiple steps, backtracking, or intermediate validation. When a single agent is required to keep all context and constraints in mind simultaneously, there is the likelihood of errors or hallucinations.

Conversely, multi-agent systems distribute reasoning across agents.

For instance, a planner agent solely focuses on breaking down objectives, while a critic agent assesses the correctness and completeness of the job.

This division enables deeper reasoning, iterative refinement, and improved outcomes for complex workflows such as software development, research synthesis, and business decision support.

c. Scalability and Parallelism

When it comes to single agent vs multi agent system architecture, scalability is a key differentiator.

Single-agent systems are inherently sequential. Even when asynchronous tools are used, the agent remains a bottleneck because all decisions flow through one reasoning loop. As workload or task diversity increases, latency and cost grow rapidly.

Multi-agent systems, on the other hand, are designed for parallel execution. They can work on different subtasks simultaneously, query multiple data sources in parallel, or independently evaluate outputs.

This parallelism delivers better performance and throughput, especially in enterprise-scale applications that must handle dozens or hundreds of tasks concurrently.

d. Reliability and Error Handling

In single-agent systems, failures are often opaque. When something goes wrong, it is difficult to determine whether the issue originated from planning, execution, or tool interaction. Error recovery usually requires rerunning the entire task.

Multi-agent systems provide fault isolation. If one agent fails or produces suboptimal output, another agent can detect, correct, or compensate for it.

For instance:

- A critic agent can flag logical inconsistencies.

- A verifier agent can reject outputs that violate constraints.

- A fallback agent can retry execution using alternative strategies.

This layered error-handling model results in systems that are more robust and production-ready.

e. Observability and Governance

In a single-agent system, observability is limited as reasoning, tool usage, and decisions are intertwined. This makes it difficult to audit behavior, measure performance, or enforce governance policies.

A multi-agent system architecture enables fine-grained observability. Each agent’s inputs, outputs, and decisions can be logged. We can evaluate performance per agent while enforcing policies at role boundaries.

This is especially critical in regulated industries where explainability, compliance, and traceability are mandatory.

When Do Single-Agent Systems Still Make Sense?

Despite their limitations, single-agent systems are not obsolete. They remain well-suited for low-risk, low-complexity use cases, simple automation tasks, or rapid prototyping and experimentation.

In fact, many production systems in 2026 follow a hybrid approach. They start with a single agent and progressively introduce additional agents as complexity grows.

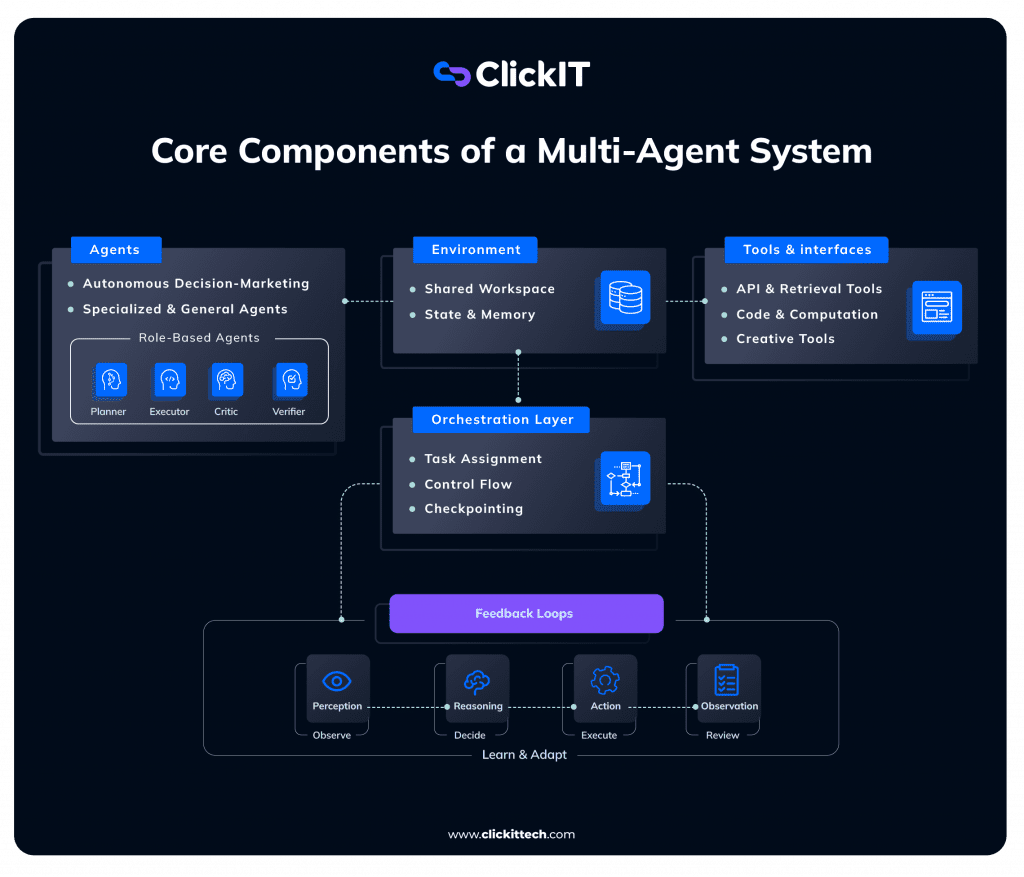

What are the Components of a Multi-Agent System Architecture?

Here are the core components of a Multi-agent system architecture:

a) Agents

Agents are the heart of any multi-agent system. They are independent computational entities capable of reasoning and action.

Agents come with the following capabilities:

i) Autonomous Decision-Making Units

Agents are autonomous by design. Each agent:

- Maintains its own internal state and context (eg. short-term conversation history, long-term vector stores, or episodic memory)

- Makes decisions based on goals, inputs, and constraints

- Executes actions without constant external supervision (eg. function calling, code execution, APIs)

This autonomy is what distinguishes agents from simple function calls or microservices. In 2026, most agents are powered by LLMs and augmented with memory, tools, and policies. As such, they can operate over extended workflows rather than single prompts.

ii. Specialized vs. General-Purpose Agents

Agents can be broadly categorized into general-purpose and specialized agents.

- General-purpose agents are flexible and capable of handling a wide range of tasks. They are useful in exploratory workflows or early-stage systems wherein requirements are not yet well-defined.

- Specialized agents are optimized for a narrow function such as retrieval, coding, evaluation, or compliance checks. These agents typically have constrained prompts, limited tool access, and clear success criteria.

For eg: a financial analyst, legal reviewer, or a researcher.

In 2026, organizations are shifting towards specialization. The reason is improved performance and consistency, reduced prompt complexity, and easy diagnosis of failure.

A good strategy is to use a mix of both. While general-purpose agents handle orchestration or ambiguity, specialized agents handle execution.

iii. Role-Based Agents (Planner, Executor, Critic, Verifier)

A role-based agent design is a common and highly effective pattern in multi-agent systems. Each role mirrors a function commonly found in human teams:

- Planner Agent: A planner agent focuses on what should be done and in what order. It translates high-level objectives into structured plans, milestones, or task graphs.

- Executor Agent: It carries out concrete actions such as calling APIs, writing code, querying databases, or interacting with external systems.

- Critic Agent: This agent is intentionally adversarial to reduce errors and hallucinations. It evaluates intermediate or final outputs for quality, logic, and alignment with goals.

- Verifier Agent: It ensures outputs meet predefined objectives such as correctness, safety, compliance, or formatting requirements.

By separating these roles, the system introduces checks and balances to significantly improve reliability and trustworthiness.

b) Environment

In a multi agent system architecture, agents do not operate in isolation. They exist within a shared environment that provides context, state, and feedback.

- Shared Environment Where Agents Operate

The environment acts as a common workspace where agents read and write shared state, exchange messages or artifacts, and observe the outcomes of actions.

This environment can be a digital workspace, a shared memory store, or a database. It can even be a real-world system such as a network or robotic platform.

- State Representation

State representation defines what the system knows at any point in time. This may include task status and progress, intermediate outputs, tool responses, or historical decisions and logs.

For eg: LangGraph’s graph state, CrewAI’s crew memory, AutoGen’s group chat memory

A well-designed state model is key to avoiding confusion, redundant work, and inconsistent behavior across agents. Modern systems often use structured state representations such as JSON schemas, knowledge graphs, or event logs. It ensures clarity and interoperability.

iii. Perception and Action Loops

In a MAS architecture, agents interact with the environment through perception–action loops.

Each agent runs a Perception -> reasoning -> action -> observation cycle, often called OODA or ReAct loops.

- Perception: Reads current environment state, new messages, and tool outputs.

- Reasoning: LLM decides the next step (plan, act, ask for clarification, terminate).

- Action: Calls tools, sends messages, updates shared state.

- Observation: Receives feedback (tool result, other agent reply, error).

The loop repeats until the task is complete or a termination condition is met. These loops allow agents to adapt dynamically rather than following static scripts and operate effectively in complex, changing environments.

c) Orchestration Layer

The orchestration layer is the backbone that turns individual agent intelligence into coordinated system behavior. It governs how agents work together.

- Agent Coordination and Task Assignment

Orchestration determines:

- Which agent handles which task

- When agents should collaborate or hand off work

- How conflicts or overlaps are resolved

This coordination can be explicit through task queues and assignments or emergent through negotiation and messaging.

- Control Flow Management

Control flow defines the execution logic of the system:

- Sequential execution for dependent tasks

- Parallel execution for independent tasks

- Conditional branching based on agent outputs

Without clear control flow, multi-agent systems can become chaotic or inefficient.

Checkpointing and Execution Persistence

Multi-agent systems frequently execute long-horizon workflows that involve dozens of steps. When a system failure occurs due to tool errors, infrastructure issues, or model instability, the entire flow should not require to be restarted.

To address this, modern orchestration layers implement checkpointing mechanisms wherein system state is persisted at key execution boundaries. For instance, LangGraph provides graph-level checkpoints that allow workflows to resume from the last successful node rather than re-consuming tokens from earlier steps.

Checkpointing is not a choice anymore but a foundational requirement, especially for production-grade multi-agent systems. It improves fault tolerance, reduces cost wastage, and enables safe retries.

- Central Orchestrator vs. Peer-to-Peer Coordination

There are two dominant orchestration models:

- Central Orchestrator: In this model, a single controller assigns tasks, monitors progress, and enforces policies. This approach is easier to reason about and debug but introduces a central point of control.

- Peer-to-Peer Coordination: Here, agents communicate directly, negotiate responsibilities, and self-organize. This model is more resilient and scalable but harder to govern.

Many real-world systems adopt a hybrid approach, combining centralized oversight with decentralized execution.

- Modern Architectural Patterns

Several architectural patterns have emerged as best practices in 2026:

- Hierarchical Pattern: High-level agents delegate tasks to lower-level agents. This mirrors organizational structures and is effective for complex planning.

- Sequential Pattern: Agents operate in a defined sequence, passing outputs downstream. This works well for pipelines such as data processing or content generation.

- Swarm Pattern: Multiple agents work in parallel on the same problem and converge on a solution through aggregation or voting. This pattern excels in exploration and optimization tasks.

d) Tools and Interfaces

Agents derive much of their power from the tools and interfaces they use.

Here are common categories of tools:

- Information retrieval: Web search, RAG, database queries

- Computation: Code interpreters, math solvers, symbolic engines

- External actions: APIs (email, calendars, CRMs, blockchains), file I/O

- Creative: Image generation, code writing, document formatting

- Verification: Unit test runners, fact-checkers

Modern frameworks standardize tool schemas and provide sandboxes for safe execution.

Eg. OpenAI-style function calling

Tool access should be explicitly scoped per agent to reduce risk and improve observability. Clear interfaces ensure that agents act in the world and not just reason about it.

e) Feedback Loops

A defining characteristic of effective multi-agent systems is the presence of feedback loops.

Agents must do more than think. They must:

- Perform actions

- Observe outcomes

- Validate results

- Refine their approach

- Feedback loops enable:

- Self-correction and learning

- Continuous improvement of outputs

- Adaptation to changing conditions

Without feedback, agents remain static and not adaptive.

Communication and Coordination in Multi-Agent System Architecture

In a multi-agent system, communication and coordination is key. In production environments, agents must communicate in a deterministic, observable, and resilient manner.

a) Structured Output and Data Contracts Between Agents

The year 2026 has seen an architectural shift from free-text agent communication toward structured outputs defined by JSON schemas.

A structured output serves as a data contract between agents. Instead of sending unstructured natural language, agents exchange messages that conform to predefined schemas specifying the required and optional fields, data types and constraints, and validation rules and error states.

Schema Versioning and Contract Stability

While JSON schemas establish strong data contracts between agents, production systems must also account for agent evolution over time.

For example, when a Planner agent is updated, downstream agents like Verifiers must not break due to incompatible schema changes.

To address this, teams should adopt:

- Explicit Schema Versioning: Each agent output should reference a versioned schema eg. plan_v1, plan_v2, etc. This allows multiple versions of a contract to coexist while agents are upgraded incrementally.

- Backward-compatible Contract Evolution: Schema changes should favor additive updates like optional fields or extended metadata rather than breaking changes. Required field removals or type changes should trigger a new schema version.

- Orchestrator-level Contract Validation: The orchestration layer should validate agent outputs against the expected schema version before routing them to downstream agents. Mismatches can be detected early and handled gracefully through fallbacks or adapters.

- Version-aware Agent Interfaces: Agents such as Verifiers should explicitly declare which schema versions they support. This allows the orchestrator to route compatible outputs or invoke transformation layers when needed

By treating agent outputs as versioned APIs, we can upgrade individual agents independently while preserving system stability as multi-agent systems scale and mature.

Benefits of structured communication

- Determinism: Downstream agents know exactly what to expect

- Validation: Messages can be programmatically verified before execution

- Interoperability: Agents written or prompted differently can still collaborate

- Observability: Logs become machine-readable and auditable

b) Agent-to-Agent Communication

Agent-to-agent communication defines how agents exchange information, delegate tasks, and coordinate actions.

Common interaction patterns

- Request–response: One agent requests an action or analysis from another

- Publish–subscribe: Agents broadcast updates that others can subscribe to

- Event-driven messaging: Agents react to state changes or system events

As a best practice, the communication design must allow agents to remain loosely coupled. Agents should understand what information they receive, not how another agent internally reasons.

This decoupling allows teams to modify, replace, or upgrade individual agents without breaking the entire system.

c) Message Passing vs. Shared State

When it comes to agent coordination, there are two primary architectural approaches:

Message Passing

In message-passing systems, agents communicate by sending explicit messages to one another.

| pros | Cons |

| Clear communication boundaries Easier to trace and debug Well-suited for distributed systems | Message orchestration can become complexLatency increases with network hops |

Message passing is ideal for enterprise workflows or regulated environments wherein traceability and isolation is the priority.

Shared State

In shared-state systems, agents read from and write to a common environment or memory store.

| pros | cons |

| Faster coordination Simplified collaboration Useful for swarm or collaborative patterns | Risk of race conditions Requires strong state management and locking strategies |

Shared state works well when agents need real-time awareness of each other’s progress, but it demands careful design to avoid inconsistencies.

d) Synchronous vs. Asynchronous Coordination

Coordination can be either synchronous or asynchronous, depending on system requirements.

Synchronous Coordination

In synchronous systems, agents wait for responses before proceeding. It enables predictable control flows and easier reasoning about dependencies.

Conversely, it comes with reduced throughput and higher latency. Synchronous coordination is useful when tasks are tightly coupled or when correctness is more important than speed.

Asynchronous Coordination

In asynchronous systems, agents operate independently and react to events or messages as they arrive.

| Pros | Cons |

| High scalability Better resource utilization Natural parallelism | Increased complexity Harder debugging |

Most large-scale systems in 2026 favor asynchronous coordination, which is often combined with timeouts, retries, and compensating actions.

e) Conflict Resolution Strategies

As agents operate autonomously, conflicts are inevitable. Common conflicts include competing task priorities, inconsistent interpretations of state, and divergent recommendations.

Robust multi-agent systems include explicit conflict resolution mechanisms such as:

- Priority-based resolution: Certain agents, such as verifiers or compliance agents, may have authority over others.

- Voting and consensus: Multiple agents propose solutions, and the system selects the best outcome based on predefined criteria.

- Critic-mediated arbitration: A critic agent evaluates competing outputs and chooses or synthesizes a final result.

- Human-in-the-loop escalation: For high-risk decisions, unresolved conflicts are escalated to a human operator.

Conflict resolution transforms disagreement from a failure mode into a feature, improving overall system quality.

How does Memory Work in a Multi-Agent Systems Architecture?

Memory is what allows agents to move beyond stateless reasoning and become context-aware, adaptive, and consistent over time.

In multi-agent systems, memory architecture is especially critical because multiple autonomous entities must reason both independently and collectively, often across long-running workflows.

A poorly designed memory layer leads to repetition, inconsistency, and hallucinations. On the other hand, a well-designed one enables coherence, learning, and coordination.

a) Short-Term Memory

Short-term memory captures the immediate context required for an agent to operate effectively within a task or interaction window. It is transient, bounded, and frequently updated.

- Task-Level Context: Task-level context includes information directly related to the current objective. For eg. user’s goal or system objective, intermediate plans and subtasks, or constraints, assumptions, and requirements.

This form of memory allows an agent to remain focused and aligned while executing multi-step workflows. For example, a planner agent may store a task graph in short-term memory, while executor agents reference only the portion relevant to their assigned tasks.

As a best practice, keep task context short-lived so that outdated goals don’t influence future decisions.

- Conversation or Execution State: Conversation and execution state tracks what has already happened. For eg. previous agent messages, tool calls and their results, errors, retries, and partial successes.

This state enables agents to avoid repeating actions, resume interrupted workflows while making decisions based on execution history. It is recommended to ensure that systems implement execution state as structured logs rather than raw text for improved traceability and recovery.

b) Long-Term Memory

Long-term memory supports persistence across sessions and tasks which means agents can accumulate knowledge and improve performance over time.

- Persistent Knowledge: It includes domain-specific facts, learned heuristics and best practices, and organizational policies and rules. Unlike short-term memory, this information is not tied to a single task. It represents what the system knows over weeks or months.

Long-term memory is particularly valuable in enterprise systems where agents must maintain consistency with evolving standards, customer preferences, or historical decisions.

- Vector Databases and Embeddings: Modern long-term memory is often implemented using vector databases and embeddings. Here, information is encoded into embeddings and stored for semantic retrieval.

This allows agents to:

- Recall relevant knowledge based on similarity

- Generalize from past experiences

- Retrieve context without exact keyword matches

Vector-based memory enables scalable recall across large knowledge bases, making it suitable for complex, evolving environments. However, retrieval must be carefully scoped. Over-retrieval introduces noise, while under-retrieval limits usefulness.

c) Shared vs. Isolated Memory

Should we share memory across agents or isolate it per agent? This is one of the most important design decisions to make in a multi-agent system architecture.

- Benefits of Shared Memory: Shared memory provides a common source of truth. Benefits include improved coordination and alignment, reduced duplication of work, and faster convergence on solutions.

For example, a shared task state allows agents to see progress in real time while shared knowledge memory ensures consistency in reasoning and outputs. Shared memory is particularly effective in collaborative or swarm-based architectures.

- Risks of Memory Contamination: Despite its advantages, shared memory introduces significant risks. For instance, memory gets contaminated when incorrect or biased information spreads across agents. It also reduces the diversity of reasoning.

If one agent makes an error and writes it to shared memory without validation, other agents may treat it as ground truth. This can cascade into systemic failures. Overfitting to early assumptions or flawed intermediate outputs is another concern.

- When to Isolate Agent Memory?

Isolated memory mitigates contamination by keeping each agent’s internal state private.

Memory isolation is recommended when:

- Agents serve adversarial or evaluative roles (eg. critics, red-team agents)

- Diversity of perspectives is desired

- Agents operate under different trust or permission levels

For example, a critic agent should not inherit the planner’s assumptions directly. Instead, it should independently evaluate outcomes.

Most robust systems adopt a hybrid approach wherein shared memory is used for validated, high-confidence information while isolated memory handles reasoning, exploration, and evaluation. This balance preserves collaboration without sacrificing robustness.

Simply put, memory architecture determines whether a multi-agent system behaves like a cohesive team or a forgetful collection of individuals. The key to building systems that are consistent, adaptive, and resilient over time is to carefully separate short-term and long-term memory while deliberately choosing when to share or isolate memory.

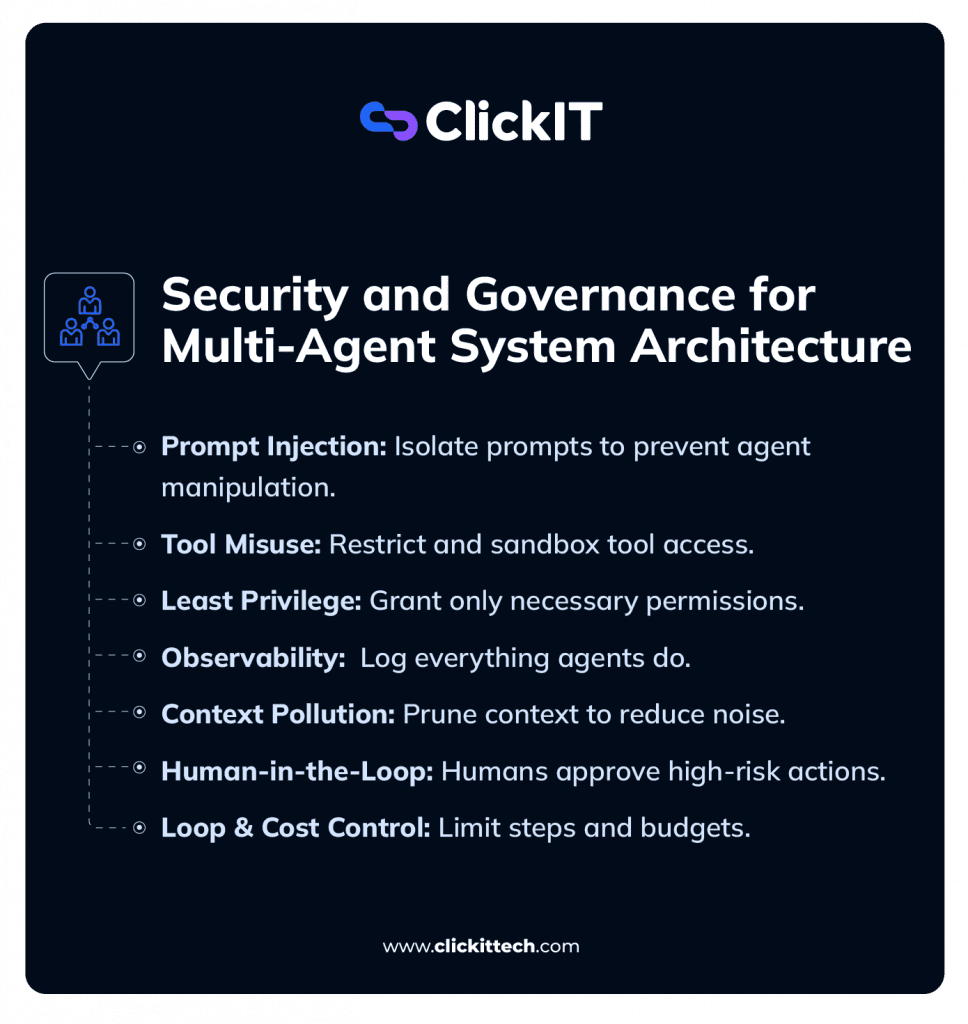

Security and Governance Considerations for Multi-Agent System Architecture

Unlike traditional software, multi-agent systems introduce autonomous decision-making, dynamic tool usage, and emergent behaviors. Each of these expands the system’s attack surface and operational risk. This is where security and governance become important.

A secure multi-agent system architecture in 2026 must assume that agents can be manipulated, make mistakes, or behave unexpectedly, and design layered safeguards.

Here are key threats to consider:

1) Prompt Injection Risks

Prompt injection is one of the most prevalent threats in agent-based systems. Agents often rely on natural language inputs from users, tools, or other agents. As such, they can be coerced into ignoring constraints or executing unintended actions.

In multi-agent systems, the risk is amplified. One compromised agent can influence others. Moreover, malicious content can propagate through shared memory or state.

How to Mitigate These Risks?

To mitigate these risks, it is recommended to strictly separate system prompts and external inputs. In addition, consider input sanitization and content filtering. Implementing a role-based instruction isolation, where agents cannot override core policies, is a good move.

Prompt injection should be treated as a systemic threat, not a single-agent problem.

2) Tool Misuse

Agents with abilities to call APIs, modify data, or execute code can introduce significant risk if tools are misused.

Common failure modes include:

- Accidental destructive actions

- Repeated or unnecessary tool calls

- Unauthorized access to sensitive systems

To reduce risk, explicitly whitelist tools per agent. In addition, ensure that tool invocation requires structured and validated inputs. Moreover, high-risk tools should be gated behind additional checks or approvals.

Sandboxing for Executor Agents

As a best practice, executor agents must operate within sandboxed environments using containerized runtimes like Docker or Firecracker.

Sandboxing ensures that:

- Code execution is isolated from host systems

- Resource usage (CPU, memory, network) is constrained

- Faulty or malicious behavior cannot propagate beyond defined boundaries

In production systems, tool access should be governed as carefully as you do with human credentials.

3) Least-Privilege Agent Design

A foundational security principle for multi agent system architecture is least privilege. Each agent should have access only to the tools it absolutely needs and operate within a narrowly scoped domain. It should be unable to escalate its own permissions.

For example, a planner agent should not have database write access, or a critic agent should not execute external actions.

Least-privilege design limits blast radius and simplifies auditing, especially when agents behave unexpectedly.

4) Observability and Logging

Without observability, governance is impossible. Multi-agent systems require comprehensive logging across agent inputs and outputs, tool invocations and parameters, inter-agent messages, and state and memory updates.

With effective observability, we can efficiently manage post-incident analysis and compliance audits while optimizing performance and costs.

As a best practice, ensure logs are structured, time-stamped, and correlated across agents to reconstruct system behavior end-to-end.

5) Context Pollution Management

Context pollution occurs when irrelevant, outdated, or low-quality information accumulates in agent context or shared memory. This leads to degraded reasoning quality, increased hallucinations, and escalated inference costs.

Context Compression and Pruning Strategies

To mitigate this, production-grade systems should implement context compression policies, such as:

- Periodic summarization of agent-to-agent conversations into structured state updates

- Retaining only decision-relevant artifacts such as plans, tool outputs, and validations while discarding raw conversational traces

- Role-specific context windows wherein each agent consumes only the subset of state relevant to its function

Context should be treated as a scarce resource, not an infinite buffer. Effective context pruning ensures that shared memory remains actionable rather than noisy. It also preserves reasoning quality while keeping token usage predictable.

6) Human-in-the-Loop for Critical Approvals

Despite advances in autonomy, certain decisions remain too risky to fully automate. As such, Human-in-the-loop (HITL) mechanisms become essential for workflows that involve financial transactions, legal or compliance decisions, or high-impact system changes.

In well-designed systems:

- Agents prepare recommendations and evidence

- Humans approve, reject, or modify actions

- Decisions are logged and fed back into the system

HITL preserves accountability while still leveraging agent efficiency.

7) Loop Prevention and Cost Control Mechanisms

One of the most expensive failure modes in multi-agent system architecture is unbounded looping, wherein agents repeatedly reason, retry, or debate without convergence.

Loop prevention mechanisms include:

- Hard limits on reasoning steps or retries

- Cost budgets per task or agent

- Convergence criteria enforced by the orchestrator

- Fallback paths to human intervention

These controls are critical not only for cost management but also for system stability.

Security and governance in multi-agent systems require intentional architectural design. By combining least-privilege principles, structured tool access, robust observability, and human oversight, organizations can deploy autonomous agent systems that are powerful yet controlled, adaptive yet accountable.

Multi-agent System Architecture Framework Selection Guide 2026

| Multi-agent Framework | Use Cases | Pros | Cons |

| CrewAI | -Role-based multi-agent teams, collaborative workflows mimicking human crews, -Rapid prototyping of team-like agents | -Cloud-native multi-agent systems, Enterprise-scale on Google -CloudIntegration with Vertex AI, Security and governance | -Less flexible for highly custom or non-hierarchical flows. -Can feel rigid or opinionated -Maintenance/scalability concerns at a very large scale -Not as deterministic as graph-based options |

| LangGraph (LangChain Ecosystem) | -Complex, long-running, stateful workflows -Branching logic Cyclical reasoning -Production-grade multi-agent orchestration with control and observability | -Excellent state management and persistence -Graph-based visual debugging (LangGraph Studio) -Deterministic control, cycles, branching, human-in-the-loop. -High flexibility & scalability -Strong for enterprise production | -Steeper learning curve -More boilerplate for simple tasks -Requires understanding graph concepts |

| Autogen (Microsoft) | -Conversational multi-agent collaboration -Dynamic group chats -Debate and emergent reasoning -Enterprise integrations (especially Azure) | -Natural conversational patterns and group dynamics -Strong for critique/debate loops Good async & event-driven support Aligns well with the Microsoft ecosystem -Flexible topologies | -Easy onboarding -Built-in hierarchical/sequential processes -Excellent for role specialization and quick MVPs -Strong observability & task delegation -Trusted by large enterprises like Oracle, Deloitte, etc. |

| OpenAI Swarm / Agents SDK | -Lightweight multi-agent orchestration -Function-calling focused -Simple handoffs -Rapid experimentation within the OpenAI ecosystem | -Extremely lightweight and minimal APINative -OpenAI integration -Encourages clean, async microservices-like design -Fast prototyping and innovation -Token-efficient in many cases | -Can become chatty/expensive (high token use) -Less structured, harder to debug at scale -Documentation & learning curve inconsistencies reported -Not ideal for strict deterministic workflows |

| Google ADK (Agent Development Kit) | -Strong enterprise features, Native Google Cloud integrationsGood for regulated industries -Supports proactive safeguards and hybrid deployments | -Strong enterprise features, Native Google Cloud integrations -Good for regulated industries -Supports proactive safeguards and hybrid deployments | -Still maturing / experimental in parts (as of 2026) -Limited built-in state management and observability Tied to OpenAI models/ecosystem -Less suited for very complex branching or long-horizon tasks |

FAQs

When it comes to the number of agents, there is no fixed value. Most production systems start with 3–5 role-based agents and expand only when the need arises. Over-agentization increases cost and complexity without guaranteed returns.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution when choosing the right multi-agent framework. It depends on your production requirements.

Here is a Quick Selection Guide for 2026:

-Need maximum control, debugging, and production reliability → LangGraph

-Want fast team/role-based setup and quick results → CrewAI

-Building conversational/debate-heavy agents → AutoGen

-Staying in the OpenAI world and want lightweight → OpenAI Swarm/Agents SDK

-Working in Google Cloud or need strong enterprise governance → Google ADK

As a best practice, go for hybrid systems. For instance, choose CrewAI for high-level roles and LangGraph underneath for orchestration. You can start with CrewAI or AutoGen for prototyping and then migrate to LangGraph for production scale.

The highest hidden cost of a multi agent system architecture is uncontrolled coordination loops. Without loop limits, budgets, and stopping criteria, costs can escalate quickly even when individual agents are inexpensive.